>>>

It’s the Inequality, Stupid

Illustrations by Jason Schneider

Illustrations by Jason SchneiderEleven charts that explain everything that’s wrong with America.

— By Dave Gilson and Carolyn Perot

Share

How Rich Are the Superrich?

A huge share of the nation’s economic growth over the past 30 years has gone to the top one-hundredth of one percent, who now make an average of $27 million per household. The average income for the bottom 90 percent of us? $31,244.

Note: The 2007 data (the most current) doesn’t reflect the impact of the housing market crash. In 2007, the bottom 60% of Americans had 65% of their net worth tied up in their homes. The top 1%, in contrast, had just 10%. The housing crisis has no doubt further swelled the share of total net worth held by the superrich.

Winners Take All

The superrich have grabbed the bulk of the past three decades’ gains.

Out of Balance

A Harvard business prof and a behavioral economist recently asked more than 5,000 Americans how they thought wealth is distributed in the United States. Most thought that it’s more balanced than it actually is. Asked to choose their ideal distribution of wealth, 92% picked one that was even more equitable.

Capitol Gain

Why Washington is closer to Wall Street than Main Street.

| member | max. est. net worth |

|---|---|

| Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.) | $451.1 million |

| Rep. Jane Harman (D-Calif.) | $435.4 million |

| Rep. Vern Buchanan (R-Fla.) | $366.2 million |

| Sen. John Kerry (D-Mass.) | $294.9 million |

| Rep. Jared Polis (D-Colo.) | $285.1 million |

| Sen. Mark Warner (D-Va.) | $283.1 million |

| Sen. Herb Kohl (D-Wisc.) | $231.2 million |

| Rep. Michael McCaul (R-Texas) | $201.5 million |

| Sen. Jay Rockefeller (D-W.Va.) | $136.2 million |

| Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) | $108.1 million |

| combined net worth: | $2.8 billion |

Congressional data from 2009. Family net worth data from 2007. Sources: Center for Responsive Politics; US Census; Edward Wolff, Bard College.

Congressional data from 2009. Family net worth data from 2007. Sources: Center for Responsive Politics; US Census; Edward Wolff, Bard College.

Who’s Winning?

For a healthy few, it’s getting better all the time.

YOUR LOSS,THEIR GAIN

How much income have you given up for the top 1 percent?

| INCOME GROUP | TOTAL LOSS/GAIN IN ANNUAL INCOME* |

AVERAGE LOSS/GAIN PER HOUSEHOLD PER YEAR* |

|---|---|---|

| TOP 1% | $673 billion more | $597,241 more |

| 96-99 | $140 billion more | $29,895 more |

| 91-95 | $29 billion more | $4,912 more |

| 81-90 | $43 billion less | $3,733 less |

| 61-80 | $194 billion less | $8,598 less |

| 41-60 | $224 billion less | $10,100 less |

| 21-40 | $189 billion less | $8,582 less |

| BOTTOM 20% | $136 billion less | $5,623 less |

* Compared to what incomes would have been had all income groups seen the same growth rate in 1979-2005 as they did during previous decades.

Source: Jacob Hacker, Yale University; Paul Pierson, UC-Berkeley

Sources

Income distribution: Emmanuel Saez (PDF)

Net worth: Edward Wolff (PDF)Household income/income share: Congressional Budget OfficeReal vs. desired distribution of wealth: Michael I. Norton and Dan Ariely(PDF)

Net worth of Americans vs. Congress: Federal Reserve (average); Center for Responsive Politics (Congress)

Your chances of being a millionaire: Calculation based on data from Wolff (PDF); US Census (household and population data)

Member of Congress’ chances: Center for Responsive Politics

Wealthiest members of Congress: Center for Responsive Politics

Tax cut votes: New York Times (Senate; House)

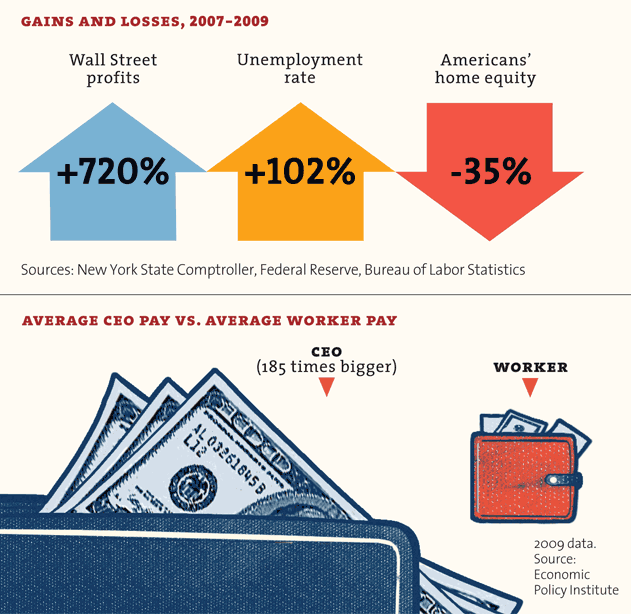

Wall street profits, 2007-2009: New York State Comptroller (PDF)

Unemployment rate, 2007-2009: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Home equity, 2007-2009: Federal Reserve, Flow of Funds data, 1995-2004 and 2005-2009 (PDFs)

CEO vs. worker pay: Economic Policy Institute

Historic tax rates: Calculations based on data from The Tax Foundation

Federal tax revenue: Joint Committee on Taxation (PDF)Read also: Kevin Drum on the decline of Big Labor, the rise of Big Business, and why the Obama era fizzled so soon.

Dave Gilson is a senior editor at Mother Jones. For more of his stories, click here. Get Dave Gilson’s RSS feed.

>>>

Why America is on the Brink of Class Warfare

(And why we should be if we aren’t.)

72% (nearly three quarters) of all American wealth is controlled by the richest 10%. (This is the highest it has ever been since statistics started being kept. This actually includes the “Robber Baron” years of the “ultra rich” before Congress started regulating business.)

The bottom ninety percent control only 28% of the wealth.

The average annual income of the top 1% in the country is $1,137,684.

The average annual income of the top 10% is $164,647.

The average annual income of the bottom 90% is $31,294.

Your chance of being a millionaire – 1 in 22.

Your chance of being a millionaire if you are in Congress – 1 in 2.

The ten richest members of Congress control over 2 billion dollars between them.

In the last two years Wall Street profits gained over 700%. The unemployment rate went up over 100%. American’s home equity went down over 35%.

The average CEO salary is 185 times that of the average worker.

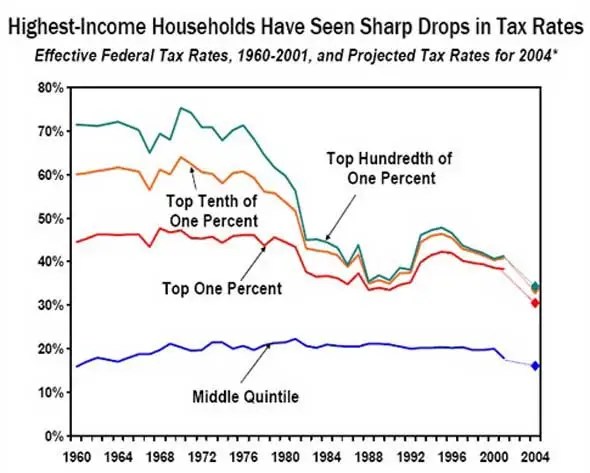

Due to tax cuts, the tax rate of the average millionaire is now the lowest it’s been since 1930.

Sources include: University of California, Berkley; Harvard Business School; Duke University; US Census; Center for Responsive Politics; Bard College; New York State Comptroller; Federal Reserve, Bureau of Labor Statistics; The Tax Foundation; The Economic Policy Institute and (amazingly) The Senate Joint Committee on Taxation.

I copied the bulk of this from an article in Mother Jones Magazine.

http://motherjones.com/politics/2011/02/income-inequality-in-america-chart-graph

Other research was done independently on the internet and can be verified from the listed sources.

>>>

Wealth, Income, and Powerby G. William DomhoffSeptember 2005 (updated January 2011)This document presents details on the wealth and income distributions in the United States, and explains how we use these two distributions as power indicators. Some of the information may come as a surprise to many people. In fact, I know it will be a surprise and then some, because of a recent study (Norton & Ariely, 2010) showing that most Americans (high income or low income, female or male, young or old, Republican or Democrat) have no idea just how concentrated the wealth distribution actually is. More on that a bit later. As far as the income distribution, the most amazing numbers on income inequality will come last, showing the dramatic change in the ratio of the average CEO’s paycheck to that of the average factory worker over the past 40 years. First, though, some definitions. Generally speaking, wealth is the value of everything a person or family owns, minus any debts. However, for purposes of studying the wealth distribution, economists define wealth in terms of marketable assets, such as real estate, stocks, and bonds, leaving aside consumer durables like cars and household items because they are not as readily converted into cash and are more valuable to their owners for use purposes than they are for resale (see Wolff, 2004, p. 4, for a full discussion of these issues). Once the value of all marketable assets is determined, then all debts, such as home mortgages and credit card debts, are subtracted, which yields a person’s net worth. In addition, economists use the concept of financial wealth — also referred to in this document as “non-home wealth” — which is defined as net worth minus net equity in owner-occupied housing. As Wolff (2004, p. 5) explains, “Financial wealth is a more ‘liquid’ concept than marketable wealth, since one’s home is difficult to convert into cash in the short term. It thus reflects the resources that may be immediately available for consumption or various forms of investments.” We also need to distinguish wealth from income. Income is what people earn from work, but also from dividends, interest, and any rents or royalties that are paid to them on properties they own. In theory, those who own a great deal of wealth may or may not have high incomes, depending on the returns they receive from their wealth, but in reality those at the very top of the wealth distribution usually have the most income. (But it’s important to note that for the rich, most of that income does not come from “working”: in 2008, only 19% of the income reported by the 13,480 individuals or families making over $10 million came from wages and salaries. See Norris, 2010, for more details.) As you read through these numbers, please keep in mind that they are usually two or three years out of date because it takes time for one set of experts to collect the basic information and make sure it is accurate, and then still more time for another set of experts to analyze it and write their reports. It’s also the case that the infamous housing bubble of the first eight years of the 21st century inflated some of the wealth numbers. So far there are only tentative projections — based on the price of housing and stock in July 2009 — on the effects of the Great Recession on the wealth distribution. They suggest that average Americans have been hit much harder than wealthy Americans. Edward Wolff, the economist we draw upon the most in this document, concludes that there has been an “astounding” 36.1% drop in the wealth (marketable assets) of the median household since the peak of the housing bubble in 2007. By contrast, the wealth of the top 1% of households dropped by far less: just 11.1%. So as of April 2010, it looks like the wealth distribution is even more unequal than it was in 2007. (See Wolff, 2010 for more details.) One final general point before turning to the specifics. People who have looked at this document in the past often asked whether progressive taxation reduces some of the income inequality that exists before taxes are paid. The answer: not by much, if we count all of the taxes that people pay, from sales taxes to property taxes to payroll taxes (in other words, not just income taxes). And the top 1% of income earners, who average over $1 million a year, actually pay a smaller percentage of their incomes to taxes than the 9% just below them. These findings are discussed in detail near the end of this document. The Wealth DistributionIn the United States, wealth is highly concentrated in a relatively few hands. As of 2007, the top 1% of households (the upper class) owned 34.6% of all privately held wealth, and the next 19% (the managerial, professional, and small business stratum) had 50.5%, which means that just 20% of the people owned a remarkable 85%, leaving only 15% of the wealth for the bottom 80% (wage and salary workers). In terms of financial wealth (total net worth minus the value of one’s home), the top 1% of households had an even greater share: 42.7%. Table 1 and Figure 1 present further details drawn from the careful work of economist Edward N. Wolff at New York University (2010).

In terms of types of financial wealth, the top one percent of households have 38.3% of all privately held stock, 60.6% of financial securities, and 62.4% of business equity. The top 10% have 80% to 90% of stocks, bonds, trust funds, and business equity, and over 75% of non-home real estate. Since financial wealth is what counts as far as the control of income-producing assets, we can say that just 10% of the people own the United States of America.

Inheritance and estate taxesFigures on inheritance tell much the same story. According to a study published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, only 1.6% of Americans receive $100,000 or more in inheritance. Another 1.1% receive $50,000 to $100,000. On the other hand, 91.9% receive nothing (Kotlikoff & Gokhale, 2000). Thus, the attempt by ultra-conservatives to eliminate inheritance taxes — which they always call “death taxes” for P.R. reasons — would take a huge bite out of government revenues (an estimated $1 trillion between 2012 and 2022) for the benefit of the heirs of the mere 0.6% of Americans whose death would lead to the payment of any estate taxes whatsoever (Citizens for Tax Justice, 2010b). It is noteworthy that some of the richest people in the country oppose this ultra-conservative initiative, suggesting that this effort is driven by anti-government ideology. In other words, few of the ultra-conservative and libertarian activists behind the effort will benefit from it in any material way. However, a study (Kenny et al., 2006) of the financial support for eliminating inheritance taxes discovered that 18 super-rich families (mostly Republican financial donors, but a few who support Democrats) provide the anti-government activists with most of the money for this effort. (For more infomation, including the names of the major donors, download the article from United For a Fair Economy’s Web site.) Actually, ultra-conservatives and their wealthy financial backers may not have to bother to eliminate what remains of inheritance taxes at the federal level. The rich already have a new way to avoid inheritance taxes forever — for generations and generations — thanks to bankers. After Congress passed a reform in 1986 making it impossible for a “trust” to skip a generation before paying inheritance taxes, bankers convinced legislatures in many states to eliminate their “rules against perpetuities,” which means that trust funds set up in those states can exist in perpetuity, thereby allowing the trust funds to own new businesses, houses, and much else for descendants of rich people, and even to allow the beneficiaries to avoid payments to creditors when in personal debt or sued for causing accidents and injuries. About $100 billion in trust funds has flowed into those states so far. You can read the details on these “dynasty trusts” (which could be the basis for an even more solidified “American aristocracy”) in a New York Times opinion piece published in July 2010 by Boston College law professor Roy Madoff, who also has a book on this and other new tricks: Immortality and the Law: The Rising Power of the American Dead (Yale University Press, 2010). Home ownership & wealthFor the vast majority of Americans, their homes are by far the most significant wealth they possess. Figure 3 comes from the Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances (via Wolff, 2010) and compares the median income, total wealth (net worth, which is marketable assets minus debt), and non-home wealth (which earlier we called financial wealth) of White, Black, and Hispanic households in the U.S.

Besides illustrating the significance of home ownership as a source of wealth, the graph also shows that Black and Latino households are faring significantly worse overall, whether we are talking about income or net worth. In 2007, the average white household had 15 times as much total wealth as the average African-American or Latino household. If we exclude home equity from the calculations and consider only financial wealth, the ratios are in the neighborhood of 100:1. Extrapolating from these figures, we see that 70% of white families’ wealth is in the form of their principal residence; for Blacks and Hispanics, the figures are 95% and 96%, respectively. And for all Americans, things are getting worse: as the projections to July 2009 by Wolff (2010) make clear, the last few years have seen a huge loss in housing wealth for most families, making the gap between the rich and the rest of America even greater, and increasing the number of households with no marketable assets from 18.6% to 24.1%. Do Americans know their country’s wealth distribution?A remarkable study (Norton & Ariely, 2010) reveals that Americans have no idea that the wealth distribution (defined for them in terms of “net worth”) is as concentrated as it is. When shown three pie charts representing possible wealth distributions, 90% or more of the 5,522 respondents — whatever their gender, age, income level, or party affiliation — thought that the American wealth distribution most resembled one in which the top 20% has about 60% of the wealth. In fact, of course, the top 20% control about 85% of the wealth (refer back to Table 1 and Figure 1 in this document for a more detailed breakdown of the numbers). Even more striking, they did not come close on the amount of wealth held by the bottom 40% of the population. It’s a number I haven’t even mentioned so far, and it’s shocking: the lowest two quintiles hold just 0.3% of the wealth in the United States. Most people in the survey guessed the figure to be between 8% and 10%, and two dozen academic economists got it wrong too, by guessing about 2% — seven times too high. Those surveyed did have it about right for what the 20% in the middle have; it’s at the top and the bottom that they don’t have any idea of what’s going on. Americans from all walks of life were also united in their vision of what the “ideal” wealth distribution would be, which may come as an even bigger surprise than their shared misinformation on the actual wealth distribution. They said that the ideal wealth distribution would be one in which the top 20% owned between 30 and 40 percent of the privately held wealth, which is a far cry from the 85 percent that the top 20% actually own. They also said that the bottom 40% — that’s 120 million Americans — should have between 25% and 30%, not the mere 8% to 10% they thought this group had, and far above the 0.3% they actually had. In fact, there’s no country in the world that has a wealth distribution close to what Americans think is ideal when it comes to fairness. So maybe Americans are much more egalitarian than most of them realize about each other, at least in principle and before the rat race begins. Figure 4, reproduced with permission from Norton & Ariely’s article in Perspectives on Psychological Science, shows the actual wealth distribution, along with the survey respondents’ estimated and ideal distributions, in graphic form.

David Cay Johnston, a retired tax reporter for the New York Times, published an excellent summary of Norton & Ariely’s findings (Johnston, 2010b; you can download the article from Johnston’s Web site). Historical contextNumerous studies show that the wealth distribution has been extremely concentrated throughout American history, with the top 1% already owning 40-50% in large port cities like Boston, New York, and Charleston in the 19th century. It was very stable over the course of the 20th century, although there were small declines in the aftermath of the New Deal and World II, when most people were working and could save a little money. There were progressive income tax rates, too, which took some money from the rich to help with government services. Then there was a further decline, or flattening, in the 1970s, but this time in good part due to a fall in stock prices, meaning that the rich lost some of the value in their stocks. By the late 1980s, however, the wealth distribution was almost as concentrated as it had been in 1929, when the top 1% had 44.2% of all wealth. It has continued to edge up since that time, with a slight decline from 1998 to 2001, before the economy crashed in the late 2000s and little people got pushed down again. Table 3 and Figure 5 present the details from 1922 through 2007.

Here are some dramatic facts that sum up how the wealth distribution became even more concentrated between 1983 and 2004, in good part due to the tax cuts for the wealthy and the defeat of labor unions: Of all the new financial wealth created by the American economy in that 21-year-period, fully 42% of it went to the top 1%. A whopping 94% went to the top 20%, which of course means that the bottom 80% received only 6% of all the new financial wealth generated in the United States during the ’80s, ’90s, and early 2000s (Wolff, 2007). The rest of the worldThanks to a 2006 study by the World Institute for Development Economics Research — using statistics for the year 2000 — we now have information on the wealth distribution for the world as a whole, which can be compared to the United States and other well-off countries. The authors of the report admit that the quality of the information available on many countries is very spotty and probably off by several percentage points, but they compensate for this problem with very sophisticated statistical methods and the use of different sets of data. With those caveats in mind, we can still safely say that the top 10% of the world’s adults control about 85% of global household wealth — defined very broadly as all assets (not just financial assets), minus debts. That compares with a figure of 69.8% for the top 10% for the United States. The only industrialized democracy with a higher concentration of wealth in the top 10% than the United States is Switzerland at 71.3%. For the figures for several other Northern European countries and Canada, all of which are based on high-quality data, see Table 4.

The Relationship Between Wealth and PowerWhat’s the relationship between wealth and power? To avoid confusion, let’s be sure we understand they are two different issues. Wealth, as I’ve said, refers to the value of everything people own, minus what they owe, but the focus is on “marketable assets” for purposes of economic and power studies. Power, as explained elsewhere on this site, has to do with the ability (or call it capacity) to realize wishes, or reach goals, which amounts to the same thing, even in the face of opposition (Russell, 1938; Wrong, 1995). Some definitions refine this point to say that power involves Person A or Group A affecting Person B or Group B “in a manner contrary to B’s interests,” which then necessitates a discussion of “interests,” and quickly leads into the realm of philosophy (Lukes, 2005, p. 30). Leaving those discussions for the philosophers, at least for now, how do the concepts of wealth and power relate? First, wealth can be seen as a “resource” that is very useful in exercising power. That’s obvious when we think of donations to political parties, payments to lobbyists, and grants to experts who are employed to think up new policies beneficial to the wealthy. Wealth also can be useful in shaping the general social environment to the benefit of the wealthy, whether through hiring public relations firms or donating money for universities, museums, music halls, and art galleries. Second, certain kinds of wealth, such as stock ownership, can be used to control corporations, which of course have a major impact on how the society functions. Tables 5a and 5b show what the distribution of stock ownership looks like. Note how the top one percent’s share of stock equity increased (and the bottom 80 percent’s share decreased) between 2001 and 2007.

Third, just as wealth can lead to power, so too can power lead to wealth. Those who control a government can use their position to feather their own nests, whether that means a favorable land deal for relatives at the local level or a huge federal government contract for a new corporation run by friends who will hire you when you leave government. If we take a larger historical sweep and look cross-nationally, we are well aware that the leaders of conquering armies often grab enormous wealth, and that some religious leaders use their positions to acquire wealth. There’s a fourth way that wealth and power relate. For research purposes, the wealth distribution can be seen as the main “value distribution” within the general power indicator I call “who benefits.” What follows in the next three paragraphs is a little long-winded, I realize, but it needs to be said because some social scientists — primarily pluralists — argue that who wins and who loses in a variety of policy conflicts is the only valid power indicator (Dahl, 1957, 1958; Polsby, 1980). And philosophical discussions don’t even mention wealth or other power indicators (Lukes, 2005). (If you have heard it all before, or can do without it, feel free to skip ahead to the last paragraph of this section) Here’s the argument: if we assume that most people would like to have as great a share as possible of the things that are valued in the society, then we can infer that those who have the most goodies are the most powerful. Although some value distributions may be unintended outcomes that do not really reflect power, as pluralists are quick to tell us, the general distribution of valued experiences and objects within a society still can be viewed as the most publicly visible and stable outcome of the operation of power. In American society, for example, wealth and well-being are highly valued. People seek to own property, to have high incomes, to have interesting and safe jobs, to enjoy the finest in travel and leisure, and to live long and healthy lives. All of these “values” are unequally distributed, and all may be utilized as power indicators. However, the primary focus with this type of power indicator is on the wealth distribution sketched out in the previous section. The argument for using the wealth distribution as a power indicator is strengthened by studies showing that such distributions vary historically and from country to country, depending upon the relative strength of rival political parties and trade unions, with the United States having the most highly concentrated wealth distribution of any Western democracy except Switzerland. For example, in a study based on 18 Western democracies, strong trade unions and successful social democratic parties correlated with greater equality in the income distribution and a higher level of welfare spending (Stephens, 1979). And now we have arrived at the point I want to make. If the top 1% of households have 30-35% of the wealth, that’s 30 to 35 times what they would have if wealth were equally distributed, and so we infer that they must be powerful. And then we set out to see if the same set of households scores high on other power indicators (it does). Next we study how that power operates, which is what most articles on this site are about. Furthermore, if the top 20% have 84% of the wealth (and recall that 10% have 85% to 90% of the stocks, bonds, trust funds, and business equity), that means that the United States is a power pyramid. It’s tough for the bottom 80% — maybe even the bottom 90% — to get organized and exercise much power. Income and PowerThe income distribution also can be used as a power indicator. As Table 6 shows, it is not as concentrated as the wealth distribution, but the top 1% of income earners did receive 17% of all income in the year 2003 and 21.3% in 2006. That’s up from 12.8% for the top 1% in 1982, which is quite a jump, and it parallels what is happening with the wealth distribution. This is further support for the inference that the power of the corporate community and the upper class have been increasing in recent decades.

The rising concentration of income can be seen in a special New York Times analysis by David Cay Johnston of an Internal Revenue Service report on income in 2004. Although overall income had grown by 27% since 1979, 33% of the gains went to the top 1%. Meanwhile, the bottom 60% were making less: about 95 cents for each dollar they made in 1979. The next 20% – those between the 60th and 80th rungs of the income ladder — made $1.02 for each dollar they earned in 1979. Furthermore, Johnston concludes that only the top 5% made significant gains ($1.53 for each 1979 dollar). Most amazing of all, the top 0.1% — that’s one-tenth of one percent — had more combined pre-tax income than the poorest 120 million people (Johnston, 2006). But the increase in what is going to the few at the top did not level off, even with all that. As of 2007, income inequality in the United States was at an all-time high for the past 95 years, with the top 0.01% — that’s one-hundredth of one percent — receiving 6% of all U.S. wages, which is double what it was for that tiny slice in 2000; the top 10% received 49.7%, the highest since 1917 (Saez, 2009). However, in an analysis of 2008 tax returns for the top 0.2% — that is, those whose income tax returns reported $1,000,000 or more in income (mostly from individuals, but nearly a third from couples) — it was found that they received 13% of all income, down slightly from 16.1% in 2007 due to the decline in payoffs from financial assets (Norris, 2010). And the rate of increase is even higher for the very richest of the rich: the top 400 income earners in the United States. According to another analysis by Johnston (2010a), the average income of the top 400 tripled during the Clinton Administration and doubled during the first seven years of the Bush Administration. So by 2007, the top 400 averaged $344.8 million per person, up 31% from an average of $263.3 million just one year earlier. (For another recent revealing study by Johnston, read “Is Our Tax System Helping Us Create Wealth?“). How are these huge gains possible for the top 400? It’s due to cuts in the tax rates on capital gains and dividends, which were down to a mere 15% in 2007 thanks to the tax cuts proposed by the Bush Administration and passed by Congress in 2003. Since almost 75% of the income for the top 400 comes from capital gains and dividends, it’s not hard to see why tax cuts on income sources available to only a tiny percent of Americans mattered greatly for the high-earning few. Overall, the effective tax rate on high incomes fell by 7% during the Clinton presidency and 6% in the Bush era, so the top 400 had a tax rate of 20% or less in 2007, far lower than the marginal tax rate of 35% that the highest income earners (over $372,650) supposedly pay. It’s also worth noting that only the first $106,800 of a person’s income is taxed for Social Security purposes (as of 2010), so it would clearly be a boon to the Social Security Fund if everyone — not just those making less than $106,800 — paid the Social Security tax on their full incomes. Do Taxes Redistribute Income?It is widely believed that taxes are highly progressive and, furthermore, that the top several percent of income earners pay most of the taxes received by the federal government. Both ideas are wrong because they focus on official, rather than “effective” tax rates and ignore payroll taxes, which are mostly paid by those with incomes below $100,000 per year. But what matters in terms of a power analysis is what percentage of their income people at different income levels pay to all levels of government (federal, state, and local) in taxes. If the less-well-off majority is somehow able to wield power, we would expect that the high earners would pay a bigger percentage of their income in taxes, because the majority figures the well-to-do would still have plenty left after taxes to make new investments and lead the good life. If the high earners have the most power, we’d expect them to pay about the same as everybody else, or less. Citizens for Tax Justice, a research group that’s been studying tax issues from its offices in Washington since 1979, provides the information we need. When all taxes (not just income taxes) are taken into account, the lowest 20% of earners (who average about $12,400 per year), paid 16.0% of their income to taxes in 2009; and the next 20% (about $25,000/year), paid 20.5% in taxes. So if we only examine these first two steps, the tax system looks like it is going to be progressive. And it keeps looking progressive as we move further up the ladder: the middle 20% (about $33,400/year) give 25.3% of their income to various forms of taxation, and the next 20% (about $66,000/year) pay 28.5%. So taxes are progressive for the bottom 80%. But if we break the top 20% down into smaller chunks, we find that progressivity starts to slow down, then it stops, and then it slips backwards for the top 1%. Specifically, the next 10% (about $100,000/year) pay 30.2% of their income as taxes; the next 5% ($141,000/year) dole out 31.2% of their earnings for taxes; and the next 4% ($245,000/year) pay 31.6% to taxes. You’ll note that the progressivity is slowing down. As for the top 1% — those who take in $1.3 million per year on average — they pay 30.8% of their income to taxes, which is a little less than what the 9% just below them pay, and only a tiny bit more than what the segment between the 80th and 90th percentile pays. What I’ve just explained with words can be seen more clearly in Figure 6.

We also can look at this information on income and taxes in another way by asking what percentage of all taxes various income levels pay. (This is not the same as the previous question, which asked what percentage of their incomes went to taxes for people at various income levels.) And the answer to this new question can be found in Figure 7. For example, the top 20% receives 59.1% of all income and pays 64.3% of all the taxes, so they aren’t carrying a huge extra burden. At the other end, the bottom 20%, which receives 3.5% of all income, pays 1.9% of all taxes.

So the best estimates that can be put together from official government numbers show a little bit of progressivity. But the details on those who earn millions of dollars each year are very hard to come by, because they can stash a large part of their wealth in off-shore tax havens in the Caribbean and little countries in Europe, starting with Switzerland. And there are many loopholes and gimmicks they can use, as summarized with striking examples in Free Lunch and Perfectly Legal, the books by Johnston that were mentioned earlier. For example, Johnston explains the ways in which high earners can hide their money and delay on paying taxes, and then invest for a profit what normally would be paid in taxes. Income inequality in other countriesThe degree of income inequality in the United States can be compared to that in other countries on the basis of the Gini coefficient, a mathematical ratio that allows economists to put all countries on a scale with values that range (hypothetically) from zero (everyone in the country has the same income) to 100 (one person in the country has all the income). On this widely used measure, the United States ends up 95th out of the 134 countries that have been studied — that is, only 39 of the 134 countries have worse income inequality. The U.S. has a Gini index of 45.0; Sweden is the lowest with 23.0, and South Africa is near the top with 65.0. The table that follows displays the scores for 22 major countries, along with their ranking in the longer list of 134 countries that were studied (most of the other countries are very small and/or very poor). In examining this table, remember that it does not measure the same thing as Table 4 earlier in this document, which was about the wealth distribution. Here we are looking at the income distribution, so the two tables won’t match up as far as rankings. That’s because a country can have a highly concentrated wealth distribution and still have a more equal distribution of income — both Switzerland and Sweden follow this pattern. So one thing that’s distinctive about the U.S. compared to other industrialized democracies is that both its wealth and income distributions are highly concentrated.

The impact of “transfer payments”As we’ve seen, taxes don’t have much impact on the income distribution, especially when we look at the top 1% or top 0.1%. Nor do various kinds of tax breaks and loopholes have much impact on the income distribution overall. That’s because the tax deductions that help those with lower incomes — such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), tax forgiveness for low-income earners on Social Security, and tax deductions for dependent children — are offset by the breaks for high-income earners (for example: dividends and capital gains are only taxed at a rate of 15%; there’s no tax on the interest earned from state and municipal bonds; and 20% of the tax deductions taken for dependent children actually go to people earning over $100,000 a year). But it is sometimes said that income inequality is reduced significantly by government programs that matter very much in the lives of low-income Americans. These programs provide “transfer payments,” which are a form of income for those in need. They include unemployment compensation, cash payments to the elderly who don’t have enough to live on from Social Security, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (welfare), food stamps, and Medicaid. Thomas Hungerford (2009), a tax expert who works for the federal government’s Congressional Research Service, carried out a study for Congress that tells us on the real-world impact of transfer payments on reducing income inequality. Hungerford’s study is based on 2004 income data from an ongoing study of a representative sample of families at the University of Michigan, and it includes the effects of both taxes and four types of transfer payments (Social Security, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, food stamps, and Medicaid). The table that follows shows the income inequality index (that is, the Gini coefficient) at three points along the way: (1.) before taxes or transfers; (2) after taxes are taken into account; and (3) after both taxes and transfer payments are included in the equation. (The Citizens for Tax Justice study of income and taxes for 2009, discussed earlier, included transfer payments as income, so that study and Hungerford’s have similar starting points. But they can’t be directly compared, because they use different years.)

As can be seen, Hungerford’s findings first support what we had learned earlier from the Citizens for Tax Justice study: taxes don’t do much to reduce inequality. They secondly reveal that transfer payments have a slightly larger impact on inequality than taxes, but not much. Third, his findings tell us that taxes and transfer payments together reduce the inequality index from .52 to .43, which is very close to the CIA’s estimate of .45 for 2008. In short, for those who ask if progressive taxes and transfer payments even things out to a significant degree, the answer is that while they have some effect, they don’t do nearly as much as in Canada, major European countries, or Japan. Income Ratios and Power: Executives vs. LaborersAnother way that income can be used as a power indicator is by comparing average CEO annual pay to average factory worker pay, something that has been done for many years by Business Week and, later, the Associated Press. The ratio of CEO pay to factory worker pay rose from 42:1 in 1960 to as high as 531:1 in 2000, at the height of the stock market bubble, when CEOs were cashing in big stock options. It was at 411:1 in 2005 and 344:1 in 2007, according to research by United for a Fair Economy. By way of comparison, the same ratio is about 25:1 in Europe. The changes in the American ratio from 1960 to 2007 are displayed in Figure 8, which is based on data from several hundred of the largest corporations.

It’s even more revealing to compare the actual rates of increase of the salaries of CEOs and ordinary workers; from 1990 to 2005, CEOs’ pay increased almost 300% (adjusted for inflation), while production workers gained a scant 4.3%. The purchasing power of the federal minimum wage actually declined by 9.3%, when inflation is taken into account. These startling results are illustrated in Figure 9.

Although some of the information I’ve relied upon to create this section on executives’ vs. workers’ pay is a few years old now, the AFL/CIO provides up-to-date information on CEO salaries at their Web site. There, you can learn that the median compensation for CEO’s in all industries as of early 2010 is $3.9 million; it’s $10.6 million for the companies listed in Standard and Poor’s 500, and $19.8 million for the companies listed in the Dow-Jones Industrial Average. Since the median worker’s pay is about $36,000, then you can quickly calculate that CEOs in general make 100 times as much as the workers, that CEO’s of S&P 500 firms make almost 300 times as much, and that CEOs at the Dow-Jones companies make 550 times as much. If you wonder how such a large gap could develop, the proximate, or most immediate, factor involves the way in which CEOs now are able to rig things so that the board of directors, which they help select — and which includes some fellow CEOs on whose boards they sit — gives them the pay they want. The trick is in hiring outside experts, called “compensation consultants,” who give the process a thin veneer of economic respectability. The process has been explained in detail by a retired CEO of DuPont, Edgar S. Woolard, Jr., who is now chair of the New York Stock Exchange’s executive compensation committee. His experience suggests that he knows whereof he speaks, and he speaks because he’s concerned that corporate leaders are losing respect in the public mind. He says that the business page chatter about CEO salaries being set by the competition for their services in the executive labor market is “bull.” As to the claim that CEOs deserve ever higher salaries because they “create wealth,” he describes that rationale as a “joke,” says the New York Times (Morgenson, 2005, Section 3, p. 1). Here’s how it works, according to Woolard:

The board of directors buys into what the CEO asks for because the outside consultant is an “expert” on such matters. Furthermore, handing out only modest salary increases might give the wrong impression about how highly the board values the CEO. And if someone on the board should object, there are the three or four CEOs from other companies who will make sure it happens. It is a process with a built-in escalator. As for why the consultants go along with this scam, they know which side their bread is buttered on. They realize the CEO has a big say-so on whether or not they are hired again. So they suggest a package of salaries, stock options and other goodies that they think will please the CEO, and they, too, get rich in the process. And certainly the top executives just below the CEO don’t mind hearing about the boss’s raise. They know it will mean pay increases for them, too. (For an excellent detailed article on the main consulting firm that helps CEOs and other corporate executives raise their pay, check out the New York Times article entitled “America’s Corporate Pay Pal”, which supports everything Woolard of DuPont claims and adds new information.) There’s a much deeper power story that underlies the self-dealing and mutual back-scratching by CEOs now carried out through interlocking directorates and seemingly independent outside consultants. It probably involves several factors. At the least, on the workers’ side, it reflects their loss of power following the all-out attack on unions in the 1960s and 1970s, which is explained in detail in an excellent book by James Gross (1995), a labor and industrial relations professor at Cornell. That decline in union power made possible and was increased by both outsourcing at home and the movement of production to developing countries, which were facilitated by the break-up of the New Deal coalition and the rise of the New Right (Domhoff, 1990, Chapter 10). It signals the shift of the United States from a high-wage to a low-wage economy, with professionals protected by the fact that foreign-trained doctors and lawyers aren’t allowed to compete with their American counterparts in the direct way that low-wage foreign-born workers are. (You also can read a quick version of my explanation for the “right turn” that led to changes in the wealth and income distributions in an article on this site, where it is presented in the context of criticizing the explanations put forward by other theorists.) On the other side of the class divide, the rise in CEO pay may reflect the increasing power of chief executives as compared to major owners and stockholders in general, not just their increasing power over workers. CEOs may now be the center of gravity in the corporate community and the power elite, displacing the leaders in wealthy owning families (e.g., the second and third generations of the Walton family, the owners of Wal-Mart). True enough, the CEOs are sometimes ousted by their generally go-along boards of directors, but they are able to make hay and throw their weight around during the time they are king of the mountain. The claims made in the previous paragraph need much further investigation. But they demonstrate the ideas and research directions that are suggested by looking at the wealth and income distributions as indicators of power. Further Information

ReferencesAFL-CIO (2010). Executive PayWatch: CEO Pay Database: Compensation by Industry. Retrieved February 8, 2010 from http://www.aflcio.org/corporatewatch/paywatch/ceou/industry.cfm. Anderson, S., Cavanagh, J., Collins, C., Lapham, M., & Pizzigati, S. (2008). Executive Excess 2008: How Average Taxpayers Subsidize Runaway Pay. Washington, DC: Institute for Policy Studies / United for a Fair Economy. Anderson, S., Cavanagh, J., Collins, C., Lapham, M., & Pizzigati, S. (2007). Executive Excess 2007: The Staggering Social Cost of U.S. Business Leadership. Washington, DC: Institute for Policy Studies / United for a Fair Economy. Anderson, S., Benjamin, E., Cavanagh, J., & Collins, C. (2006). Executive Excess 2006: Defense and Oil Executives Cash in on Conflict. Washington, DC: Institute for Policy Studies / United for a Fair Economy. Anderson, S., Cavanagh, J., Klinger, S., & Stanton, L. (2005). Executive Excess 2005: Defense Contractors Get More Bucks for the Bang. Washington, DC: Institute for Policy Studies / United for a Fair Economy. Central Intelligence Agency (2010). World Factbook: Country Comparison: Distribution of family income – Gini index. Retrieved October 26, 2010 from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2172rank.html. Citizens for Tax Justice (2010b). State-by-State Estate Tax Figures: Number of Deaths Resulting in Estate Tax Liability Continues to Drop. Retrieved December 13, 2010 from http://www.ctj.org/pdf/estatetax2010.pdf. Citizens for Tax Justice (2010a). All Americans Pay Taxes. Retrieved April 15, 2010 from http://www.ctj.org/pdf/taxday2010.pdf. Dahl, R. A. (1957). The concept of power. Behavioral Science, 2, 202-210. Dahl, R. A. (1958). A critique of the ruling elite model. American Political Science Review, 52, 463-469. Davies, J. B., Sandstrom, S., Shorrocks, A., & Wolff, E. N. (2006). The World Distribution of Household Wealth. Helsinki: World Institute for Development Economics Research. Domhoff, G. W. (1990). The Power Elite and the State: How Policy Is Made in America. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter. Gross, J. A. (1995). Broken Promise: The Subversion of U.S. Labor Relations Policy. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Hungerford, T. (2009). Redistribution effects of federal taxes and selected tax provisions. Washington: Congressional Research Service. Johnston, D. C. (2010b). United in Our Delusion. Retrieved October 12, 2010 from http://www.tax.com/taxcom/taxblog.nsf/Permalink/UBEN-8A6TUW?OpenDocument. Johnston, D. C. (2010a). Tax Rates for Top 400 Earners Fall as Income Soars, IRS Data. Retrieved February 23, 2010 from http://www.tax.com/taxcom/features.nsf/Articles/0DEC0EAA7E4D7A2B852576CD00714692?OpenDocument. Johnston, D. C. (2009, December 21). Is Our Tax System Helping Us Create Wealth? Tax Notes, pp. 1375-1377. Johnston, D. C. (2006, November 28). ’04 Income in U.S. Was Below 2000 Level. New York Times, p. C-1. Keister, L. (2005). Getting Rich: A Study of Wealth Mobility in America. New York: Cambridge University Press. Kenny, C., Lincoln, T., Collins, C., & Farris, L. (2006). Spending Millions to Save Billions: The Campaign of the Super Wealthy to Kill the Estate Tax. Washington, DC: Public Citizen / United for a Fair Economy. Kotlikoff, L., & Gokhale, J. (2000). The Baby Boomers’ Mega-Inheritance: Myth or Reality? Cleveland: Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. Lukes, S. (2005). Power: A Radical View (Second ed.). New York: Palgrave. Madoff, R. D. (2010, July 12). America Builds an Aristocracy. New York Times, p. A-19. Morgenson, G. (2005, October 23). How to slow runaway executive pay. New York Times, Section 3, p. 1. Norris, F. (2010, July 24). Off the Charts: In ’08 Downturn, Some Managed to Eke Out Millions. New York Times, p. B-3. Norton, M. I., & Ariely, D. (2010, forthcoming). Building a better America – one wealth quintile at a time. Perspectives on Psychological Science. Polsby, N. (1980). Community Power and Political Theory (Second ed.). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Russell, B. (1938). Power: A New Social Analysis. London: Allen and Unwin. Saez, E. (2009). Striking It Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States (Update with 2007 Estimates). Retrieved August 28, 2009 from http://elsa.berkeley.edu/~saez/saez-UStopincomes-2007.pdf. Saez, E., & Piketty, T. (2003). Income Inequality in the United States, 1913-1998. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118, 1-39. Shapiro, I., & Friedman, J. (2006). New, Unnoticed CBO Data Show Capital Income Has Become Much More Concentrated at the Top. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Stephens, J. (1979). The Transition from Capitalism to Socialism. London: Macmillan. Wolff, E. N. (1996). Top Heavy. New York: The New Press. Wolff, E. N. (2004). Changes in household wealth in the 1980s and 1990s in the U.S. Working Paper No. 407. Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. Wolff, E. N. (2007). Recent trends in household wealth in the United States: Rising debt and the middle-class squeeze. Working Paper No. 502. Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. Wolff, E. N. (2010). Recent trends in household wealth in the United States: Rising debt and the middle-class squeeze – an update to 2007. Working Paper No. 589. Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. Wrong, D. (1995). Power: Its Forms, Bases, and Uses (Second ed.). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| All content ©2011 G. William Domhoff, unless otherwise noted. Unauthorized reproduction prohibited. Please direct technical questions regarding this Web site to Adam Schneider. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

>>

We hear a lot these days about how government spending has led to a deficit that could pose a major long-term threat if it goes unaddressed. It’s true that government has of late grown under both Democratic and Republican presidents. But deficit hawks often sidestep a no-less important trend: In recent decades, tax rates–especially for the rich–have been on the decline by historical standards. Everyone likes getting a tax cut, but it’s worth remembering that the shrinking of tax revenue has contributed to the deficit problem, just as spending has.

Via Felix Salmon, a fascinating (and strangely beautiful!) chart, compiled by Stephen Von Worley at the DataPointed blog, drives home that point, and a few others.

What to make of all those swirling lines? The chart shows how tax burdens for different income levels have fluctuated over the last century, adjusted for inflation. Blue areas represent a historically low tax burden for a specific income level, while red areas represent a historically high burden.

So in a nutshell, the chart shows that until around 1940, tax burdens were low for everyone, in historical terms. Then they rose sharply for everyone until about 1970. At that point, the rich and poor began to diverge. Those making around $10,000 to around $50,000 per year enjoyed a comparatively low-tax period in the 70s, but by the early 80s they were taxed slightly higher than the historical average. In the 2000s, their tax rate came back down a bit. By contrast, those making more than roughly $200,000 a year saw a sharp decrease in their tax burden starting in the 80s. That trend has continued to this day.

It’s clear, then, that across the board, today’s tax rates are low by historical standards–and for the rich they’re very low. If the bottom of the chart showed more red and less blue, our deficit problem would be a lot more manageable.

The chart also has implications for another topic we’ve written about here before–wealth and income inequality. As you can see, no one’s taxes today are particularly high by historical standards, but those making $1 million or more per year–that is, roughly the top 1 percent–enjoy the lowest burden, relative to past rates.

At a time when a horde of stats indicates that the gap between rich and poor has widened into chasm–and when Congress and the White House are set to argue again later this year about whether to permanently extend the Bush tax cuts for the rich–it’s well worth keeping this bigger picture in mind.

<><>

Tax Cuts Offer Most for Very Rich, Study Says

Top of Form

Bottom of Form

Published: January 8, 2007

WASHINGTON, Jan. 7 — Families earning more than $1 million a year saw their federal tax rates drop more sharply than any group in the country as a result of President Bush’s tax cuts, according to a new Congressional study.

The study, by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, also shows that tax rates for middle-income earners edged up in 2004, the most recent year for which data was available, while rates for people at the very top continued to decline.

Based on an exhaustive analysis of tax records and census data, the study reinforced the sense that while Mr. Bush’s tax cuts reduced rates for people at every income level, they offered the biggest benefits by far to people at the very top — especially the top 1 percent of income earners.

Though tax cuts for the rich were bigger than those for other groups, the wealthiest families paid a bigger share of total taxes. That is because their incomes have climbed far more rapidly, and the gap between rich and poor has widened in the last several years.

The study offers ammunition to supporters and opponents of Mr. Bush’s tax cuts, which are all but certain to touch off a battle between the president and the Democrats who just took control of Congress.

Democratic leaders have taken pains to avoid an immediate fight over the tax cuts, most of which are scheduled to expire at the end of 2010. But Democrats are looking for ways to increase revenue well before then, in part because they want to spend more on education and energy without increasing the deficit.

Economists and tax analysts have long known that the biggest dollar value of Mr. Bush’s tax cuts goes to people at the very top income levels. One reason is that two of his signature measures, tax cuts on investment income and a steady reduction of estate taxes, overwhelmingly benefit the wealthiest households.

But the Congressional study offers additional insight because it incorporates information about what people paid in 2004, the first year in which taxpayers could take full advantage of the cuts on stock dividends and capital gains.

The study estimates that the effective federal income tax rate, which excludes payroll taxes for Social Security and Medicare, declined modestly for people in the middle- and lower-income categories.

Families in the middle fifth of annual earnings, who had average incomes of $56,200 in 2004, saw their average effective tax rate edge down to 2.9 percent in 2004 from 5 percent in 2000. That translated to an average tax cut of $1,180 per household, but the tax rate actually increased slightly from 2003.

Tax cuts were much deeper, and affected far more money, for families in the highest income categories. Households in the top 1 percent of earnings, which had an average income of $1.25 million, saw their effective individual tax rates drop to 19.6 percent in 2004 from 24.2 percent in 2000. The rate cut was twice as deep as for middle-income families, and it translated to an average tax cut of almost $58,000.

In its report, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that the overall effective federal tax rate edged up to 20 percent in 2004, from 19.8 percent the year before.

But even with that increase, Americans faced lower tax rates than any time since 1979. If President Bush has his way, those rates could decline even more as the estate tax on inherited wealth is gradually phased out by the start of 2010.

Mr. Bush and his Republican allies in Congress want to permanently extend that tax cut and almost all of the others that Congress passed in his first term. The cost of doing that would be more than $1 trillion over the next decade, a cost that would hit the Treasury at the same time that the spending on old-age benefits for retiring baby boomers begins to soar.

The budget office offered little commentary on its new estimates, but many of its numbers spoke for themselves.

The report shows that a comparatively small number of very wealthy households account for a very big share of total tax payments, and their share increased in the first four years after Mr. Bush’s tax cuts.

The top 1 percent of income earners paid about 36.7 percent of federal income taxes and 25.3 percent of all federal taxes in 2004. The top 20 percent of income earners paid 67.1 percent of all federal taxes, up from 66.1 percent in 2000, according to the budget office.

By contrast, families in the bottom 40 percent of income earners, those with incomes below $36,300, typically paid no federal income tax and received money back from the government. That so-called negative income tax stemmed mainly from the earned-income tax credit, a program that benefits low-income parents who are employed.

Put another way: rich families were the undisputed winners from President Bush’s tax cuts, but people in the bottom half of the earnings scale were not paying much in taxes anyway.

<>

Monday, November 22, 2010

Can we blame income inequality on Republicans?

Part V

The Great Divergence by Noah

9 The percentage of the labor force that used computers increased at a faster rate in the 1980s than in the 1990s, but it wasn’t until the mid-to-late late ‘90s that a majority of workers used computers.

Overall, pre-tax income increased 1.42 percent annually for the 20th percentile (poor and lowermiddle-class people) and 2 percent annually for the 95th percentile (upper-middle-class and rich people). The White House during this period was occupied by five Democrats (Truman, Kennedy, Johnson, Carter, Clinton) and six Republicans (Eisenhower, Nixon, Ford, Reagan, Bush I, Bush II). Bartels plotted out what the inequality trend would have been had only Democrats been president. He also plotted out what the trend would be had only Republicans been president.on politics,” Hacker and Pierson point out in their new book, Winner-Take-All Politics, “only a fairly small fraction is directly connected to electoral contests. The bulk of it goes to lobbying….” Corporations now spend more than $3 billion annually on lobbying, according to official records cited by Hacker and Pierson (which, they note, understate true expenditures). That’s nearly twice what corporations spent a decade ago.

Until recently, the consensus among academics—even most liberal ones—was quite different. Economists argued that the Great Divergence was the result not of Washington policymaking but of larger “exogenous” (external) and “secular” (long-term) forces. In June, the Congressional Budget Office calculated that spending by the federal government made up 23 percent of U.S. gross domestic product, after averaging 18.5 percent during the previous four decades. But even with federal spending at this unusually high level (necessitated by a severe recession), Washington’s nut remains less than one-quarter the size of the economy. Most of that nut is automatic “entitlement” spending over which Washington policymakers seldom exert much control. Brad DeLong, a liberal economist at Berkeley, expressed the prevailing view in 2006: “[T]he shifts in income inequality seem to me to be too big to be associated with anything the government does or did.”

My Slate colleague Mickey Kaus took this argument one step further in his 1992 book The End of Equality, positing that income inequality was the inevitable outgrowth of ever-more-ruthlessly efficient markets, and that government attempts to reverse it were certain to fail. “[Y]ou cannot

decide to keep all the nice parts of capitalism,” he wrote, “and get rid of all the nasty ones.” Instead, Kaus urged liberals to combat social inequality by nurturing egalitarian civic institutions (parks, schools, libraries, museums) and by creating some new ones (national health care, national service, a revived WPA) that remove many of life’s most important activities from the

“money sphere” altogether.

Finding ways to increase social equality is an important goal, and Kaus’s book remains a smart and provocative read. But the academic consensus that underlay Kaus’s argument (and Long’s more modest one) has lately started to crumble.

Economists and political scientists previously resisted blaming the Great Divergence on government mainly because it didn’t show up when you looked at the changing distribution of federal income taxes. Taxation is the most logical government activity to focus on, because it is literally redistribution: taking money from one group of people (through taxes) and handing it

over to another group (through government benefits and appropriations).

Another compelling reason to focus on taxation is that income-tax policy has changed very dramatically during the last 30 years. Before Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980, the top income tax bracket stood at or above 70 percent, where it had been since the Great Depression. (In the

Compression, as the economy boomed and income inequality dwindled, the top bracket resided at a level that even most Democrats would today call confiscatory. Reagan dropped the top bracket from 70 percent to 50 percent, and eventually pushed it all the way down to 28 percent. Since then, it has hovered between 30 percent and 40 percent. If President Obama lets George

W. Bush’s 2001 tax cut expire for families earning more than $250,000, as he’s expected to do, Tea Partiers will call him a Bolshevik. But at a whisker under 40 percent (up from 35), the top bracket would remain 30 to 50 percentage points below what it was under Presidents Eisenhower, Nixon, and Ford. That’s how much Reagan changed the debate.

But tax brackets, including the top one, tell you only the marginal tax rate, i.e., the rate on the last dollar earned. The percentage of total income that you actually pay in taxes is known as theeffective tax rate. That calculation looks at income taxed at various rates as you move from one

bracket to the next; it figures in taxes on capital gains and pensions; it figures in “imputed taxes” such as corporate and payroll taxes paid by your employer (on the theory that if your boss didn’t give this money to Uncle Sam he’d give it to you); and it removes from the total any money the

federal government paid you in Social Security, welfare, unemployment benefits, or some other benefit. Reagan lowered top marginal tax rates a lot, but he lowered top effective tax rates much less—and certainly not enough to make income-tax policy a major cause of the Great Divergence.

In 1979, the effective tax rate on the top 0.01 percent (i.e., rich people) was 42.9 percent, according to the Congressional Budget Office. By Reagan’s last year in office it was 32.2 percent. From 1989 to 2005 (the last year for which data are available), as income inequality continued to climb, the effective tax rate on the top 0.01 percent largely held steady; in most

years it remained in the low 30s, surging to 41 during Clinton’s first term but falling back during his second, where it remained. The change in the effective tax rate on the bottom 20 percent (i.e., poor and lower-middle-class people) was much more dramatic, but not in a direction that would

increase income inequality. Under Clinton, it dropped from 8 percent (about where it had stood since 1979) to 6.4 percent. Under George W. Bush, it fell to 4.3 percent.

Measuring tax impacts is not an exact science. There are many ways to define rich, poor, and middle class, and many variables to consider. Some experts have looked at the same data and concluded that effective tax rates have gone up slightly for people at high incomes. Others concluded they’ve gone down. The larger point is that you can’t really demonstrate that U.S. tax

policy had a large impact on the three-decade income inequality trend one way or the other. The inequality trend for pre-tax income during this period was much more dramatic. That’s why academics concluded that government policy didn’t affect U.S. income distribution very much.

But in recent years a few prominent economists and political scientists have suggested looking at the question somewhat differently. Rather than consider only effective tax rates, they recommend that we look at what MIT economists Frank Levy and Peter Temin call “institutions and norms.”

It’s somewhat vague phrase, but in practice what it mostly means is “stuff the government did, or didn’t do, in more ways than we can count.” In his 2007 book, The Conscience of a Liberal, Princeton economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman concludes that there is “a strong circumstantial case for believing that institutions and norms … are the big sources of rising inequality in the United States.” Krugman elaborated in his New York Times blog:

[T]he great reduction of inequality that created middle-class America between 1935 and

1945 was driven by political change; I believe that politics has also played an important

role in rising inequality since the 1970s. It’s important to know that no other advanced

economy has seen a comparable surge in inequality.

Proponents of this theory tend to make their case not by measuring the precise impact of each thing government has done but rather by charting strong correlations between economic trends and political ones. In his 2008 book Unequal Democracy, Larry Bartels, a Princeton political scientist, writes:

[T]he narrowly economic focus of most previous studies of inequality has caused them to

miss what may be the most important single influence on the changing U.S. income

distribution over the past half-century—the contrasting policy choices of Democratic and

Republican presidents. Under Republican administrations, real income growth for the

lower- and middle-classes has consistently lagged well behind the income growth rate for

the rich—and well behind the income growth rate for the lower and middle classes

themselves under Democratic administrations.

Bartels came to this conclusion by looking at average annual pre-tax income growth (corrected for inflation) for the years 1948 to 2005, a period encompassing much of the egalitarian Great Compression and all of the inegalitarian Great Divergence (up until the time he did his research).

Bartels broke down the data according to income percentile and whether the president was a Democrat or a Republican. Figuring the effects of White House policies were best measured on a one-year lag, Bartels eliminated each president’s first year in office and substituted the year following departure. Here is what he found:

In Democrat-world, pre-tax income increased 2.64 percent annually for the poor and lowermiddle-class and 2.12 percent annually for the upper-middle-class and rich. There was no Great Divergence. Instead, the Great Compression—the egalitarian income trend that prevailed through the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s—continued to the present, albeit with incomes converging less rapidly than before. In Republican-world, meanwhile, pre-tax income increased 0.43 percent annually for the poor and lower-middle-class and 1.90 percent for the upper-middle-class and rich. Not only did the Great Divergence occur; it was more greatly divergent. Also of note: In Democrat-world pre-tax income increased faster than in the real world not just for the 20th percentile but also for the 40th, 60th, and 80th. We were all richer and more equal! But in Republican-world, pre-tax income increased slower than in the real world not just for the 20th percentile but also for the 40th, 60th, and 80th. We were all poorer and less equal! Democrats also produced marginally faster income growth than Republicans at the 95th percentile, but the difference wasn’t statistically significant. (More on that in a future installment.)

What did Democrats do right? What did Republicans do wrong? Bartels doesn’t know; in Unequal Democracy he writes that it would take “a small army of economists” to find out. But since these are pre-tax numbers, the difference would appear to be in macroeconomic policies. (Tne clue, Bartels suggests, is that Republicans always worry more than Democrats about

inflation.) Bartels’ evidence is circumstantial rather than direct. But so is the evidence that smoking is a leading cause of lung cancer. We don’t know exactly how tobacco causes the cells inside your lungs to turn cancerous, but the correlation is strong enough to convince virtually every public health official in the world.

Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson, political scientists at Yale and Berkeley, respectively, take a slightly different tack. Like Bartels and Krugman, they believe that government action (and inaction) at the federal level played a leading role in creating the Great Divergence. But the culprit, they say, is not so much partisan politics (i.e., Republicans) as institutional changes in the

way Washington does business (i.e., lobbyists). “Of the billions of dollars now spent every year

According to Hacker and Pierson, industry began to mobilize in the early 1970s in response to liberalism’s political ascendancy (which didn’t end when Richard Nixon entered the White House in 1969):

The number of corporations with public affairs offices in Washington grew from 100 in 1968 to over 500 in 1978. In 1971, only 175 firms had registered lobbyists in Washington, but by 1982, 2,500 did. The number of corporate [political action committees] increased

from under 300 in 1976 to over 1,200 by the middle of 1980. […] The Chamber [of Commerce] doubled in membership between 1974 and 1980. Its budget tripled. The National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) doubled its membership between

1970 and 1979.

examples and make arguments that are a little more speculative. We’ll look at one such example in the next installment.

The resultant power shift, they argue, affects Democrats and Republicans like.Academics who believe that government policies are largely responsible for the Great Divergence don’t breeze past the relevant mechanisms. Bartels writes at length about repeal of the estate tax, and the decline of the minimum wage; Hacker and Pierson about financial deregulation. But their approach to them is more impressionistic than comprehensive. They offer

Liberal politicians and activists have long argued that the federal government caused the Great Divergence. And by “federal government,” they generally mean Republicans, who have controlled the White House for 20 of the past 30 years, after all. A few outliers even argue that for Republicans, creating income inequality was a conscious and deliberate policy goal.

Posted by Michele at 1:52 AM

Update Just for Fun

0 comments:

<>

border=0 v:shapes=”_x0000_i1032″> v:shapes=”_x0000_i1033″>

Monday, October 25th, 2010

The

Fraudulent Case for the Benefits of Wealth Inequality

by Chris Lehmann on October 25th, 2010

Americans, having seen the fruits

of their productive lives waste away over the past decade in a free-market

fantasia, have evidently resorted to the most efficient psychic adjustment on

offer. They steadfastly refuse to believe that we live in conditions of dire

wealth inequality—while also persisting in the belief that the comparatively

level social order of their fond imagining needs to be more equal still. The

sheer scale of this fancy calls to mind the epitaph

that William Holden delivers for Gloria Swanson’s character in Billy Wilder’s

classic study in Hollywood delusion, Sunset Boulevard: “Life, which

can be strangely merciful, had taken pity on Norma Desmond. The dream she had

clung to so desperately had enfolded her.”

Of course, Norma Desmond was packed off to the hoosegow, and in all

likelihood the sanitarium, once the cameras panned away. Today’s Americans have

to continue indulging their socioeconomic delusions amid savage inequalities

that make just about every facet of their own lives worse.

But not to worry: Bloomberg reporter Drake Bennett is

on hand to break the whole paradox down and reassure us that, even

as we kid ourselves about the basic operation of economic reward and

punishment, we surely continue to live in the best of all possible worlds.

Bennett first sums up the research of psychologists Michael I. Norton of

Harvard Business School and Dan Ariely of Duke University, who’d polled a

research sample of respondents on both the existing and ideal levels of wealth

inequality in these United States with the sobering finding that “Americans

think they live in a far more equal country than they in fact do.” Ariely and

Bennett discovered that most of their respondents believed Americans in the top

quintile of our wealth hierarchy controlled 59 percent of the nation’s wealth;

the actual figure is around 84 percent. These same Pollyannas believed that the

bottom 20 percent of Americans held 3.7 percent of the country’s wealth, while

the actual figure is 0.1 percent.

Now, if these same respondents were handicapping horse races or Oscar pools,

they would be considered abject failures, blowing the tremendously significant

top-quintile figures by a bit less than a third, and the lower figure by a

factor of, oh, 37. Their perfect-world scenario for inequality would transform

the United States into a society “like Sweden, only more so,” Bennett notes,

with the top 20 percent owning 32 percent of the wealth, and the bottom 20

percent tripling their already imaginary stake up to 10 percent.

So, screw the Tea Party—everyone meet on Wall Street for the paralyzing

French-style general strike and ensuing social revolution! Well, not

so fast, Bennett cautions: The American public, even as it dulls its jobless

ennui with fantasies of a robust welfare state, also has a curious tolerance

for enormous levels of political cognitive dissonance:

Studies have also shown that voters have an impressive ability to absorb

information that contradicts their beliefs without letting it change their

minds. People support the abstract goal of equality, it seems, while staunchly

opposing specific government measures—whether increasing tax rates or limiting

executive pay—designed to impose it.

In other words, the lodestar Reaganite faith of government-shredding,

tax-squelching economic policy continues to tantalize the U.S. public in

roughly the same fashion that the dogma of the divine right of kings kept

generations of Old World peasants from revolting—even though Ronald Reagan

himself continued both to hike

government spending and raise

taxes. (Also, it turns out that whole Excalibur thing was pretty

much a put-on, as well.)

And that, Bennett explains, is the unique genius of our terminal

cluelessness about one of the most important issues of our age: Believing that

we inhabit a more just social order—and militantly not caring should we

encounter the all-too abundant evidence to the contrary—is what keeps us from

raising a dread populist hew and cry about what is a non-issue anyway. In fact,

Brother Bennett preaches in the fashion of hordes of free-market propagandists

everywhere, wealth inequality is a good thing: It bespeaks the robust

dynamism of an innovative economy, where the quest for marginal competitive

advantage greases the skids for everyone else. After all, Bennett explains, the

comparatively flatter distribution of American wealth in the Eisenhower years

came about in large part because “the wealthiest earners paid far more in

taxes,” with the top marginal rate for incomes over $400,000 topping out at 90

percent. So all together now, in the requisite scowling, world-weary mien of a

journalist employed by one

of the richest men on Earth: “Any attempt to reimpose that sort of

tax rate today would lead to a flight of wealth and talent from the U.S. And

with apologies to the social scientists, other ideas for dramatically reducing

the income gap are in short supply.”

Hmm, where have we heard that “talent flight” mantra before? That’s

right—from the defenders of the outlandish executive bonuses doled out under the misbegotten

early days of the TARP bailouts. It would indeed be a shame to have

to send the Fabrice

Tourres of the world packing for greener pastures. And with apologies

to Bloomberg savants, there are plenty of ideas for reducing our objectively

perilous levels of wealth inequality, from single-payer health care to

nationalized universities to unionized workplaces. Most industrialized western

democracies have all these things, and as a result, the pain of massive

economic contractions like the one we’ve been enduring is actually less lethal

in exotic far-off lands like Canada

and France.

But of course, that’s just part of the free-market scaremongering kit when